Agricultural Extension Education In Indonesian The Colonial Period 1900-1941

Indonesia is an agricultural country. Its agrarian products enter international trade. Traders have introduced Indonesian agricultural products since the ancient path of international trade. Agricultural production systems that have been running for centuries have formed a different kind of humidity throughout the vast territory of Indonesia.

Wertheim described three Indonesian civilizations that influenced production systems and trade patterns: (1) The hinterland of Central Java and East Java have long known as the pattern of irrigated rice fields. This pattern has been taking place in much of Central Java and East Java since thousands of years ago. The population living in the rice fields in the area under investigation was very tight. Village life was mainly based on a closed economic system. Peasants have become accustomed to producing the necessities of daily life in their household, (2) Along the coasts of Java, Sumatra, the Malay Peninsula, estuaries of large rivers in Kalimantan, and the eastern islands, developed coastal kingdoms. These coastal cities had very close contact with other port cities in Hindustan, India, China, Japan, and others. The nobles controlled the port cities and international trade, especially in the spice trade, (3) The inland regions of the coastal kingdoms of Sumatra and Kalimantan were very differ ent from irrigated and densely populated areas such as Central Java and East Java. In this area, the land was still spread out wide. The population was still sparse. Farmers grew pepper beside food crops. Some parts of West Java until 1600 were still a continuation of Sumatra’s forests. Priangan peasants were not a permanent peasant. They were not active in trade. They handed over their agricultural prod ucts to the king in Banten (Wertheim, 1999, pp. 2-3).

Spices from Indonesia pushed Euro peans to come to Indonesia. When Dutch traders had difficulty getting spices in Eu rope, they were moved to get spices direct ly from Indonesia (Atmosudirdjo, 1957, p.57). When the Dutch traders first arrived at the port of Banten on June 22, 1596, they found that the port was already crowded with traders from various coun tries. There were traders from Turkey, China, Bengal, Arabia, Persia, Gujarat, and others carrying merchandise from their homeland. Meanwhile, Indonesian traders, in addition to spices, also offered chicken, meat, and various kinds of fruits (Van Leur, 2015, p. 3).

The Dutch people who came to Ja va were initially only in the form of trade partnerships in the Netherlands. They then shared in a container called Verenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (VOC) in 1602 (Atmosudirdjo, 1957, p. 60). The VOC developed into a large trad ing company, which not only controlled the trade routes but also controlled the political sphere. The big ambition to dom inate the political field had shifted its trad ing interests so that its position in interna tional trade had weakened. Early in the 19th century, the VOC was taken over by the Dutch government. H.W. Daendels was sent as Governor-General (1808-18011) to establish a modern government called the Dutch East Indies (Onghokham, 1983, p. 6).

The Dutch East Indies colonial gov ernment controlled Indonesia’s trade routes. It managed Indonesian agricultural products that sold well in international markets. Land and agricultural power were used more to produce export crops such as sugar, indigo, coffee, tea, and rub ber. Food crops that were produced to meet the needs of life of farmers received less attention. Large plantations with their growing plants were growing rapidly. From these export crops, Western planta tion companies made huge profits (Fasseur, 1975).

Meanwhile, the yields of food crops produced to meet the daily needs of peas ants continued to decline. This condition caused economic dualism. The foreign economy developed rapidly, while the in digenous economy suffered a setback (Boeke, 1953). At the end of the 19th century, the rural economy, especially in Java, experienced an extraordinary decline. The pov erty of the indigenous population had led to the birth of an ethical policy movement. Despite its enthusiasm to improve the economy of the Indonesian people, this movement was overcome by various inter ests. Therefore the limits of understanding about ethical politics also varied. Some understood the ethical movement as the political movement to abolish guardian ship, the politics of increasing welfare, ethical imperialism, and the political movement for the benefit of the Dutch export industry (Locher-Scholten, 1981).

The essence of these movements was the demand for the Dutch govern ment to pay the debt of gratitude to the Indonesian people. One of the results of the ethical policy movement was the for mation of the Department of Agriculture (Department van Landbouw, Nijverheid, en Handel) in 1903. In a speech around the founding of the Department of Agriculture in Tweede Kamer, Van Kol accused the Dutch government of neglecting its obliga tion to pay attention to the fate of indige nous agriculture (Het Inlandsche Landbouw Department in Tweede Kamer, 18 July 1904). This department was established to enhance the people’s agricultural economy (Staten Generaal, 6 July 1904). To be able to provide technical knowledge to indige nous peasant, in 1911, this department established the agricultural extension ser vice (Landbouwvoorlichtingsdient) (Koens, 1925, p. 26). This agricultural extension service then continued until Indonesia’s independence. Through intensive agricul tural counseling, the New Order govern ment even succeeded in self-sufficiency in rice in the 1980s. However, in the period after that, Indonesia returned to being an importer of rice and other agricultural products such as corn and soybeans (Davidson, 2018).

The first article about Landbouwvoor lichtingsdient was written by A.J. Koens, ‘De Landbouwvoorlichtingsdienst en de Aanstaande Bestuursreorganisatie’ in Land bouw, Tijdschrift der Vereeniging van Land bouwconsulenten in Nederlandsch-Indie.I- 1926-’26. P. 79-108. Koens explained that the Landbouwvoorlichtingsdient initially can not be described as a service. In the De partment of van Landbouw, Nijverheid, en Handel, this service was a function of the Landbouw afdeeling. It only took shape after Bestuurshervoormingswet 1922 (Koens, 1956, p. 26).

Research on rural agricultural edu cation (desa landbouw onderwijs) was car ried out by Vroon. In his article entitled ‘Beschouwing over het desalandbouw-onderwijs in Priyangan’ he criticized Koens, who standardized rural agricultural education in Java. Taking the case in Priangan (West Java), Vroon argued that the village agriculture school education method as practiced by Koens in Bondowoso (East Java), apparently cannot be implemented in Priangan villages. Peasant communities in rural Priangan prefer sending their chil dren to religious schools rather than send ing them to Western schools (Vroon, 1930).

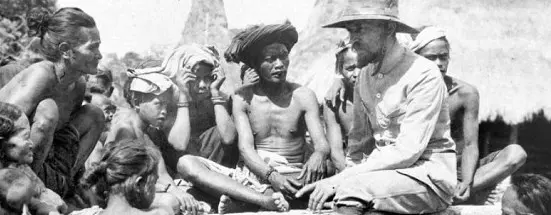

Agricultural counseling by Prince was seen as part of the expansion of small holder agriculture and colonial govern ment intervention in efforts to improve the quality of smallholder agrarian products. The aim of expanding smallholder agricul ture was to increase agricultural produc tion and the welfare of the Indonesian population. The strategy of disseminating information carried out by the agricultural extension service by introducing technical agricultural knowledge. In his analysis of the work of the agricultural extension ser vice, Prince concluded that the agricultur al extension service focused more on in troducing agricultural technology, but paid less attention to what the local com munity needed (Prince, 1993). A research conducted by Wahyono and Huda focused more on the develop ment of agricultural extension institutions in the Dutch East Indies. The results of his study concluded that although agricultural extension had been established since 1911, the results of his work were practically only visible after the 1920s. This institu tion concretely found the format of its work after the formation of the provinces in Java, which were established under the Government’s Renewal Act (Bestuurs hervormingswet) 1922. With the establish ment of the province in Java, which began in West Java in 1928, the responsibility of the agricultural extension service was giv en to the province (Wahyono and Huda, 2015).

Other reports on the agricultural extension were scattered in various coloni al newspapers written between 1900 and 1942, which were the references in this writing. Besides, there were two books on agricultural extension, each written by the agriculture department team (1978) and by Syamsuddin Abbas (1995). Both of these books only presented narratives of the milestones of agricultural extension from 1905 until the year the book was written. All of the previous writings above did not at any time specifically discussed education or agricultural courses that were given in stages to the peasants’ groups in the countryside.

This paper examines one segment of the history of Indonesian agriculture that has not been widely discussed by histori ans, namely how the Dutch East Indies colonial government prepared extension experts who would provide counseling about agriculture. It is an effort that can improve the quality of agricultural prod ucts of the indigenous peasant so that it can improve their agricultural products. Therefore, this paper can contribute to developing Indonesian historiography, especially in the history of agricultural extension education that had not received much attention from historians today.