The Development of Agrarian Culture for Farmers in Indonesia by the Dutch Colonials 1900-1941

Agricultural Development Education Colonial Period

MLS and Cultuur School is not to accommodate ordinary farmer children. Native children of the pedestal group only followed HIS. Whereas regular peasant children generally attended education at Volksschool or public school for three years, then they can continue their education to Vervolksschool for two years. This school was established in a self-sufficient manner by village institutions. In some schools, the Dutch East Indies government provided subsidies.

The language of instruction of this school used local languages, and in some cases, schools used Malay. Vervolksschool graduates can continue Normaalschool to be prepared to become teachers at Volksshool or Vervolksschool. The quality of this school was under HIS, ELS, or HCS. Therefore Vervolksschool graduates cannot continue to Cultuurschool. To enter Cultuurschool, they must attend an intermediate education called Schakelschool. These conditions indicated that the difficulty of being a student of an agricultural school (Cultuurschool). On the other hand, the government needed many students from agriculture to meet the needs of agricultural extension workers.

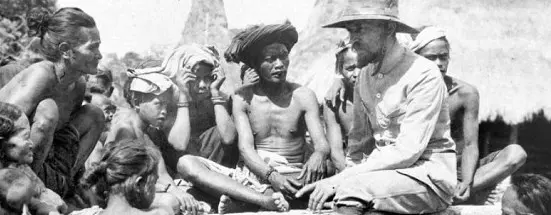

To be able to establish contact with farmers required a large number of liaison workers. Agricultural extension assistants who were already familiar with the local community tried to form core staff in each village. Farmers who were advanced, successful and had social status can work together as agents to educate other farmers. In this way, many farmers in the village will function as extension agents. The more advanced farmers, the more ready they were to make improvements. From this effort, a counseling education system was then prepared. This education will be integrated with the Volksschool people’s school. To be able to provide suitable agricultural learning materials, adequate agricultural teachers were needed.

For this reason, agricultural extension assistants provided agricultural courses to public school teachers. These teachers were prepared to provide agricultural counseling in the villages. Through this simple agricultural education, liaison was born, which involved as much as possible in agricultural extension. They formed peasant groups. These liaison officers were appointed as chair of peasant groups with about 20 people. After Indonesian independence until the end of the New Order, it was also known as a “group of listeners and viewers” (Klompencapir) who were so active in moving farmers to achieve government programs. Televisi Republik Indonesia (TVRI), the only television that existed at that time, aired the group of programs intensively. The members of this group will work together to sell their products, set up their barns to store seeds, and so on. Superior rice seedlings should not be eaten. If the seeds were eaten, the superior rice species would disappear (Onze landbouw voorlichtingsdient, April 17, 1941).

The next step was to increase the teacher’s knowledge output from Normaalschool in agriculture. For this reason, in 1929, in the town of Batu, East Java, an opleiding voor Landbouwonderwijs was established. Several teachers from Normaalsechool were selected and told to study at the school for one year. They were educated in various kinds of plants. For a year, they rolled their sleeves. The pen stem was thrown away and replaced with a hoe. In 1930-31 Opleiding voor Landbouw in Batu graduated 20 peasant teachers who were then placed as low school teachers in their respective regions, in Sumatra and Java. In 1931 another Opleiding voor Landbouonderwij school was established in Tegalgondo, near Solo (Central Java). Teachers from Sumatra and West Java were sent to Batu, while those from Central, East Java, and Madura were sent to Tegalgondo. Furthermore, the teacher who had graduated from Opleiding voor Landbouwonderwijs was appointed as a low school teacher (Pemimpin Tani, No. 7-VI, July 1932).

The Adjunct landbouwconsulent in each district also conveyed knowledge about agricultural business to teachers of grade 2 village schools (vervolksschool) in the form of courses. Agricultural knowledge taught was various things about agriculture that were suitable to the conditions of the local community. Course material must be following the practice in the field, which can be seen and witnessed by the local community. The course was given after teaching hours (between 4-6 pm). The course was held twice a week, two hours for each meeting. The course lasted for two years. After completing the course, the teachers can teach farming materials to the children of peasants in the village where they lived. Those who were allowed to take part inagriculture were those who were old and had intense energy to carry out work as peasants. Some of the course participants were already peasant, and some work to help their parents as peasant (Sinar Tani, July 1926).

The material provided was soil science, plant science, the science of fertilizing, and corporate science. While the course material for children was working on cultivating land, planting rice and secondary crops, planting other young plants, planting tea, raising livestock, counting in terms of land use, and matters relating to land tenure rights (Koens, 1926b, pp. 27-29).

The lessons emphasized the agricultural situation of each course. Participants enriched with field trips in the experimental gardens and practice. The teachers participating in this course then become the course leaders in their respective villages. They got agricultural courses according to the state of their village. Place of practice, wherever possible, was on the land owned by parents, of course, participants. Also, the agricultural extension service opened the land for demonstrations and experimental gardens for practice. This practice in the agricultural extension service land was held twice a week. Courses in these villages were held in 16 places in Bondowoso district. According to Resident Bondowoso, A.H. Neys, such courses affected the level of knowledge of peasant in the villages, among others were the increasingly widespread use of plows in planting rice, increasing demand for seeds for improved seeds, green manure, and artificial fertilizers, as well as improvements in handling and drying tobacco (Memorie van Overgave Resident Bondowoso, AH Neys, 1929).

Village school (Vervolksschool) students in Tamanan (East Java) got plant science lessons from their teacher named N. Soemopranoto. They got lessons in cultivating plants. In Karangmelok village, a teacher named Prawirokusumo also taught the same to class 5 village school students (Sinar Tani No. 7, year 1, January 1927). Agricultural courses in the Landbouw Bondowoso/Besuki area were spread over 18 places. The number of participants reached 205 participants, or on average, each course was attended by nine participants. Beyond that, there were still requests to open agricultural courses, but they cannot be fulfilled (Sinar Tani, 1927).

In Soreang (Bandung), and Tanjungsari (Sumedang) West Java, were established village agriculture schools, to provide agricultural courses to indigenous people and got financial assistance from the government. The school provided theoretical and practical agricultural teaching for two years. Unlike in East Java, the attention of residents to take courses in this area was very less. There were few students, and each year was decreasing. After a few years, the school was finally closed and moved to another place, namely in Cangkring. However, here too, the public’s attention was lacking.

The school in Tanjungsari was founded in 1914, with 28 students. Until 1918 this school had saved 122 people. In 1920 by Koens the school was put into one class for two years and did not accept new students. In Sumedang, in 1920, an agriculture course was held for village teachers. The course was given in the afternoon was attended by 50 participants. In the village of Sabandar Cianjur, an agricultural school had also been established on the initiative of the regent of Cianjur. This school did not last long. In 1918 the school was reopened. When it was opened, the course was attended by 30 people, but one year later the number remained half, while the new students who registered were only 15 people. The following year there were fewer requests, so they had to close (Memorie van Overgave Resident Priyangan, L. De. Streurs, 1921).

CONCLUSION

The peasant empowerment program in the villages during the colonial administration in Indonesia was carried out through agricultural extension. The knowledge and skills of extension workers were obtained through education. Agricultural education that was first introduced in the agricultural system in Indonesia was the Agricultural College in Wageningan. Graduates from this school initially carried out their functions as Landbouwconsulen (agricultural consultants). They worked on European plantations. Thus, their focus was on developing export crops that sell well in the international market. When the agriculture department was formed in 1905, they were the primary movers of the department. However, when they were assigned to carry out the function of increasing indigenous agricultural production, it cannot do much. They generally did not understand the economic system of the indigenous peasant. The problem of local language and culture was also an obstacle for them. That was why the Dutch East Indies government felt the need to develop a system of agricultural education for indigenous people.

Agricultural education for the first indigenous people was established in Bogor called Midelbare Landbouw School. A top-level agricultural school. Then formed an elementary-level agricultural school (junior high school level) called the Cultuur School. Graduates of this school were prepared to become skilled workers in the forestry sector, agricultural supervisors, and agricultural instructors. At the village level, agricultural extension education was carried out through agricultural courses. These courses were given to village school teachers (Vervolksschool), outside their teaching hours. These Vervolksschool teachers then became agents in village community development by teaching agricultural materials to fifth-grade Vervolksschool students, and peasants groups. Such an extension system continued until Indonesia gained independence, at least until the New Order government. At that time, there was a first-level agricultural school and a top-level agricultural school. In addition, farmers’ groups were formed in the villages. These groups then became the drivers of development in rural communities, so that Indonesia succeeded in achieving food self-sufficiency.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Abbas, S. (1995). 90 Tahun Penyuluhan Pertanian di Indonesia (1905-1995). Jakarta: Departemen Pertanian.

Boeke, J. H. (1953). Economics and economic policy of dual societies as exemplified by Indonesia. Haarlem: Tjeenk Willink & Zoon.

Booth, A. (1988). Agricultural development in Indonesia. Sydney: Allen and Unwin.

Circular of the Head of Agriculture Section dated December 18, 1923, Number of 1816.

Davidson, J. S. (2018). Then and Now: Campaigns to Achieve Rice Self-Sufficiency in Indonesia. Bijdragen tot de taal, land en volkenkunde, 174-2-3, 188-215.

Geertz, C. (1984). Involusi Pertanian: Proses perubahan ekologi di Indonesia. Jakarta: Yayasan Obor Indonesia.

Kertosumo, S. (1926). Sedikit Keterangan dan Maksoednja Cursus Tani Rendah Oentoek Anak-Anak Tani dalam Kareisdenan Besoeki. Sinar Tani, 1(2).

Koens, J. A. (1925a). Drie Ontdekkingen Op Het Gbied Van Het Eenvoudig Landbouwonderwijs. Landbouw: Tijdschrift der Vereeniging van Landbouwconsulenten in Nederlandsch-Indie, 1 (26).

Koens, J. A. (1925b). De Landbouwvoorlicht- ingsdienst En De Aanstaande Bestuurshervormings Organisatie. Landbouw: Tijdschrift der Vereeniging van Land- bouwconsulenten in Nederlandsch-Indie, 1 (26).

Landbouw. (1935). Landbouw: Landbourkundig tijdschrief voor Nederlandsche-Indie, 10 (1), 176-177.

Lekkerkerker, T. J. (1921). Het Landbouwonderwijs in Nederlandsch-Indie. Batavia: Deukerij Ruycrok & Co.

Organisatie. Landbouw: Tijdschrift der Vereeniging van Landbouwconsulenten in Nederlandsch-Indie, 1 (26).

Onze Landbouw Voorlichtingsdient. De Indische Courant, April 17, 1941.

Pedoman Tani. V (1), January 1930. Pertoeloengan dari kantor Landbow. (1926). Sinar Tani, 4.

Sinar Tani. I (1), January 1927.

Sinar Tani. II (4), April 1927.